Exciting studies on human reproductive cells are profiled in Nature:

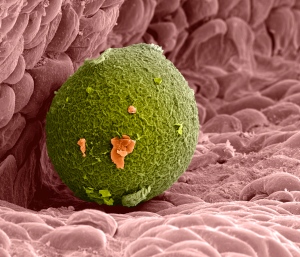

Even though the reproductive age for humans is around 15–45 years old, the precursor cells that go on to produce human eggs or sperm are formed much earlier, when the fertilized egg grows into a tiny ball of cells in the mother’s womb. This ball of cells contains ‘pluripotent stem cells’ — blank slates that can be programmed into any type of cell in the body — and researchers are hoping to use these stem cells to treat various conditions, including infertility.

But little is known about the early developmental stages of human gametes — owing to the sensitivity of working with human tissue — and most work in this area has been conducted using mice. In a Nature Cell Biology paper today1, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, trace the development of early germ cells in human fetuses of between 6 to 20 weeks and analysed when genes were turned on or off.

The DNA within these early germ cells carries ‘epigenetic modifications’ — structural changes that do not affect the DNA sequence itself but do affect the way that genes are expressed. These changes may have accumulated during the parents’ lives, and need to be erased during the fetal stage. The study found two major events that wipe out, or reprogram, epigenetic modifications. Most of this reprogramming happened before 6 weeks, but the authors found a second event that completes the reprogramming after 6 weeks.