Here at GOLLYGEE! we’ve been following the news on bees and electric fields.

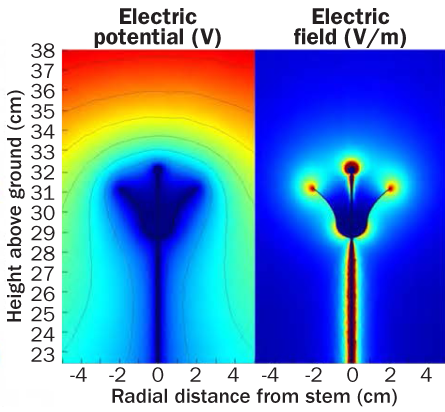

We learned last month that flowers use electric fields to guide bees their way. Bees pick up a positive charge from the static they encounter while flying through the air. Flowers, like most plants, conduct electricity toward the ground and have a negative charge at their surfaces. When bees encounter a flower, the negatively charged pollen is attracted to their positive charge. And when they leave, other bees can tell the flower was just visited because of the reduced electric field.

Yesterday, Ed Yong at Not Exactly Rocket Science reported that bees also use electric fields to facilitate social interaction:

Greggers created Pavlov’s bees. He exposed them to artificial electric fields that mimicking those found in the hive, before giving them a rewarding sip of nectar. Soon, he found that the field alone was enough to make them extend their tongues in anticipation of a tasty treat, just like Pavlov’s dogs salivating at a the sound of a bell.

Greggers found that the bees detect these fields with their flagella—the very tips of their antennae. Picture a bee, dancing away in a tightly packed hive with many neighbours in close proximity. As it waggles, it also vibrates its wings. As the dancer’s positively-charged wing get closer to a neighbour’s positively-charged antenna, it produces a force that physically repels the antenna. As the dancer’s wing swings back to its original position, the neighbour’s antenna bounces back too. With their electric fields, the bees can move each other’s body parts without ever making contact. (Sure, the beating wing also pushes air past a neighbour’s antenna, but Greggers found that the force produced by the incoming electric field is ten times stronger.)

The bee detects these forces with small touch-sensitive fibres in the joints of their antennae, which send electrical signals towards the insect’s brain. If Greggers immobilised the joints by covering the antennal joints with wax, the bees couldn’t learn to associate electric fields with nectar rewards.

These signals from the fibres are intercepted and processed by a structure called Johnston’s organ within the antennae. By recording the activity of neurons in this organ, Greggers showed that it does indeed fire when an electrically charged object—like a Styrofoam ball—is brought close to the flagellum.

Head over to Not Exactly Rocket Science for more. Or read the research paper here.