Over at Aeon, Robert D Martin debunks a persistent myth of biology. Many people, including scientists, believe that during fertilization, sperm are in competition, racing to be the first to fertilize an egg. Because sperm competition is observed in chimpanzees and other mammals closely related to humans, people think that the same holds true for men. But Robert points out all the evidence against this theory.

First, human sperm contains a higher proportion of deformed or abnormal sperm compared to chimpanzees. If sperm were in competition to fertilize an egg, you would expect for there to be fewer nonmotile sperm than are observed. Chimpanzees, have relatively few abnormalities in their sperm cells.

Secondly, much of the sperm’s transport to the ovary is achieved passively. Through the womb and oviducts, a wafting and pumping motions propel sperm through the female tract. And in fact much of the selection of intact sperm is happens because of environment in the woman’s vagina and cervix.

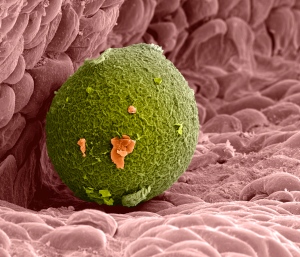

Many sperm do not even make it into the neck of the womb (cervix). Acid conditions in the vagina are hostile and sperm do not survive there for long. Passing through the cervix, many sperm that escape the vagina become ensnared in mucus. Any with physical deformities are trapped. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of sperm migrate into side-channels, called crypts, where they can be stored for several days. Relatively few sperm travel directly though the womb cavity, and numbers are further reduced during entry into the oviduct. Once in the oviduct, sperm are temporarily bound to the inner surface, and only some are released and allowed to approach the egg.

Robert continues from there, explaining what happens when too many sperm reach an egg and how cervical mucus can contain and release viable intact sperm for up to 5-10 day. The essay is quite interesting and well worth a read, so I won’t spoil it all. It’s an interesting counterargument to the manly notion that the best sperm gets the egg.