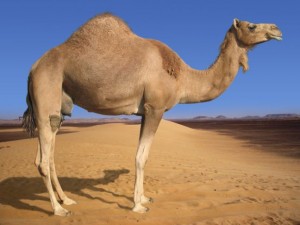

Genomic studies are helping researchers determine what is unique about these dessert dwelling mammals. It turns out it is mostly their metabolism. From Scientific American:

Camels, as ruminants like cattle and sheep, digest food by chewing the cud. But many of the Bactrian genome’s rapidly evolving genes regulate the metabolic pathway, suggesting that what camels do with the nutrients after digestion is a whole different ball game. “It was surprising to me that they had significant difference in the metabolism,” says Kim Worley, a molecular geneticist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. The differences could point to how Bactrians produce and store energy in the desert.

The work shows that camels can withstand massive blood glucose levels owing in part to changes in genes that are linked to type II diabetes in humans. The Bactrians’ rapidly evolving genes include some that regulate insulin signaling pathways, the authors explain. A closer study of how camels respond to insulin may help to unravel how insulin regulation and diabetes work in humans. “I’m very interested in the glucose story,” says Brian Dalrymple, a computational biologist at the Queensland Bioscience Precinct in Brisbane, Australia.

The researchers also identified sections of the genome that could begin to explain why Bactrian camels are much better than humans at tolerating high levels of salt in their bloodstreams. In humans, the gene CYP2J controls hypertension: suppressing it leads to high blood pressure. However, camels have multiple copies of the gene, which could keep their blood pressure low even when they consume a lot of salt, suggest the authors of the latest work.

The study appears in Nature Communications.