A while back some scientists thought they had discovered a bacteria that could thrive on arsenic. They hypothesized that arsenic was being incorporated into the organism’s molecules in place of phosphorus without any problem. This was later discovered to be incorrect. A paper in Nature Magazine details how bacteria discriminate between arsenic and phosphorus. From Scientific American:

“This work provides in a sense an answer to how GFAJ-1 (and related bacteria) can thrive in very high arsenic concentrations,” say Tobias Erb and Julia Vorholt of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, co-authors of the latest paper, who were also co-authors on a follow-up paper that cast doubt on the initial arsenic-life claims.

The researchers looked at five types of phosphate-binding protein — which bind phosphate in a molecular pathway that brings it into the cells — from four species of bacteria. Two of the bacterial species were sensitive to arsenate and two were resistant to it. To test how effective these proteins were at discriminating between phosphate and arsenate, the researchers put them in solution with a set amount of phosphate and different concentrations of arsenate for 24 hours, and then checked which of the molecules the proteins would bind to.

Their threshold for when ‘discrimination’ broke down was when 50% of the proteins ended up bound to arsenate — indicating that the ability to discriminate had been overwhelmed. Even in solutions containing 500-fold more arsenate than phosphate, all five proteins were still able to preferentially bind phosphate. And one protein, from the Mono Lake bacterium, could do so at arsenate excesses of up to 4,500-fold over phosphate.

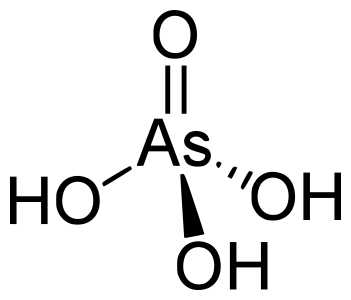

The paper includes detailed structures of both phosphate and arsenate bound to bacterial protein. You can see how the arsenate’s larger size impedes protein binding. Please check out the source link for more.