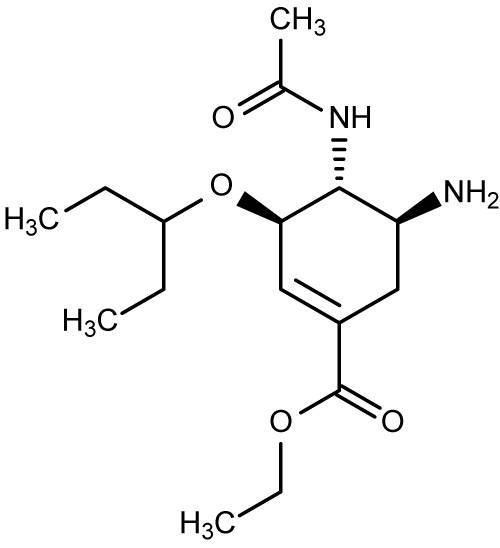

HIV medications

A baby, born in Mississippi 2.5 years ago appears to have been cured of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. She is the first child, and only the second person ever, to have been thought to be cured of the infection. The cure was acheived thanks to an aggressive and early treatment with antiretroviral drugs just 30 hours after she was born. From NPR:

Gay decided to begin treating the child immediately, with the first dose of antivirals given within 31 hours of birth. That’s faster than most infants born with HIV get treated, and specialists think it’s one important factor in the child’s cure.

In addition, Gay gave higher-than-usual, “therapeutic” doses of three powerful HIV drugs rather than the “prophylactic” doses usually given in these circumstances.

Over the months, the baby thrived, and standard tests could detect no virus in her blood, which is the normal result from antiviral treatment.

Doctors then lost track of the baby for several months, as the mother went through “life changes.” But when they regained contact with the child, it showed a surprising lack of HIV virus. Again from NPR:

Gay expected to find that the child’s blood was teeming with HIV. But to her astonishment, tests couldn’t find any virus.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh, my goodness, I’ve been treating a child who’s not actually infected,’ ” Gay says. But a look at the earlier blood work confirmed the child had been infected with HIV at birth. So Gay then thought the lab must have made a mistake with the new blood samples. So she ran those tests again.

The results of this isolated event are prompting researchers to begin planning studies on whether this early and aggressive treatment can be more widely applied. It would have huge implications for AIDS treatment in the developing world where many children are infected with HIV during birth.

Also see coverage at the New York Times.