Last week on Slate, Bethany Brookshire explains the neurotransmitter dopamine and how it effects many different chemical processes:

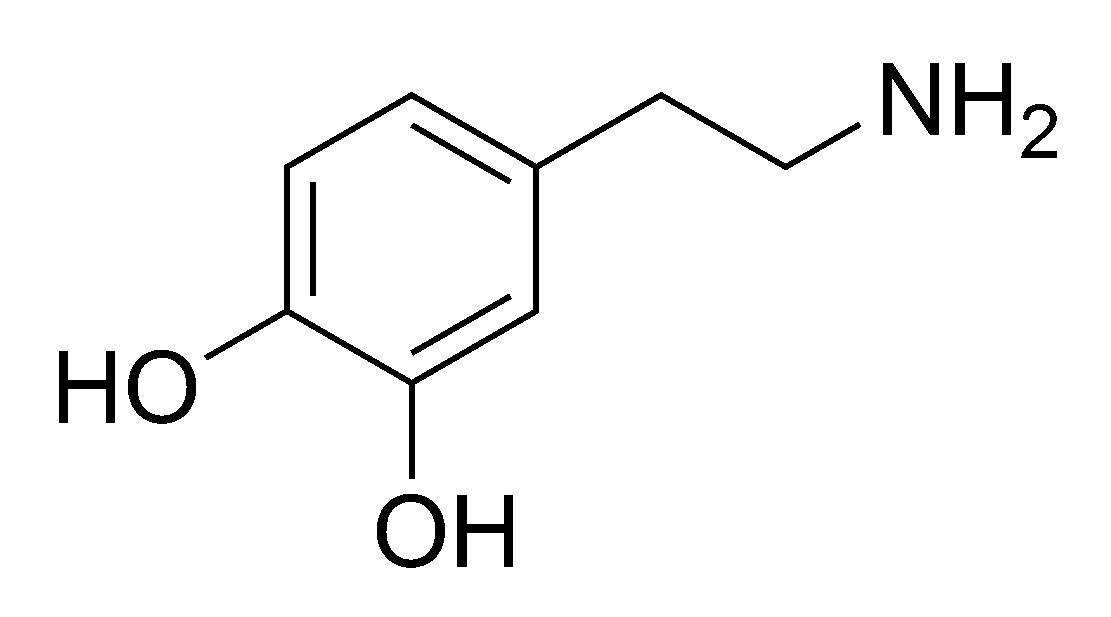

What is dopamine? Dopamine is one of the chemical signals that pass information from one neuron to the next in the tiny spaces between them. When it is released from the first neuron, it floats into the space (the synapse) between the two neurons, and it bumps against receptors for it on the other side that then send a signal down the receiving neuron. That sounds very simple, but when you scale it up from a single pair of neurons to the vast networks in your brain, it quickly becomes complex. The effects of dopamine release depend on where it’s coming from, where the receiving neurons are going and what type of neurons they are, what receptors are binding the dopamine (there are five known types), and what role both the releasing and receiving neurons are playing.

It has far more roles in the brain to play. For example, dopamine plays a big role in starting movement, and the destruction of dopamine neurons in an area of the brain called the substantia nigra is what produces the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Dopamine also plays an important role as a hormone, inhibiting prolactin to stop the release of breast milk. Back in the mesolimbic pathway, dopamine can play a role in psychosis, and many antipsychotics for treatment of schizophrenia target dopamine. Dopamine is involved in the frontal cortex in executive functions like attention. In the rest of the body, dopamine is involved in nausea, in kidney function, and in heart function.