The New York Times ran an obituary commemorating the life of Dr. Yvette Francis-McBarnette. I had never heard of her but found her life story inspirational, especially for budding minority scientists.

Dr Yvette Fay Francis-McBarnette

Yvette immigrated to New York City from Jamaica with her parents and at 14 years old she began studies at Hunter College. After completing a bachelor’s degree in physics, she began a master’s degree in chemistry at Columbia University. Then she went on to be come only the second black woman to earn a medical degree from Yale University.

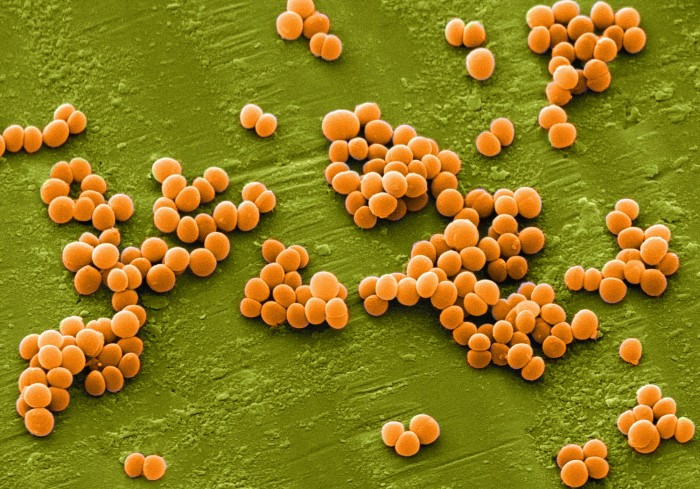

As a physician, she made tremendous progress in studying and treating sickle cell anemia in young patients. Sickle cell disease deforms the shape of red blood cells, making them rigid and harder to pass through capillaries. It can lead to oxygen deprivation in organs and tissues and also severe pain. The disease is more prevalent in black and Mediterranean populations.Yvette pioneered new antibiotic treatments for the disease and established the Foundation for Research and Education in Sickle Cell Disease. And she did all of this work during the 1950s and 60s when women had fewer opportunities and less support than exists today, doubly so for black women.