About a week ago, NASA presented compelling evidence of flowing water on The Red Planet. The water flows foster hope that there may yet be life to discover on Mars. Scientific American discusses the hardest part of discovering the first Martians: preventing contamination from Earth.

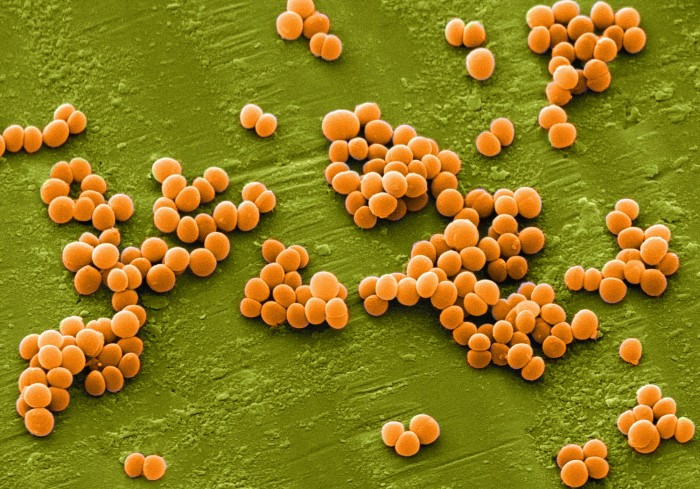

The problem is not exploding rockets, shrinking budgets, political gamesmanship or fickle public support—all the usual explanations spaceflight advocates offer for the generations-spanning lapse in human voyages anywhere beyond low Earth orbit. Rather, the problem is life itself—specifically, the tenacity of Earthly microbes, and the potential fragility of Martian ones. The easiest way to find life on Mars, it turns out, may be to import bacteria from Cape Canaveral—contamination that could sabotage the search for native Martians.

Certain areas of Mars are designated as “Special Regions” by the Committee on Space Research, or COSPAR, and restricted from earthly visitors. These special regions appear to have the right topography and geothermal profiles to support life. By prohibiting visitors, astronomers hope to preserve any potential extraterrestrial life. But are these designations enough to protect Martian soil and species from Earth’s most relentless invaders?

Read more at Scientific American.