The New York Times has an interesting write up on the discovery of bacteria species in one of the frozen lakes of Antarctica. The bacteria were found about four feet deep in the sediment of Lake Whillans. They survive apparently requiring little oxygen or exposure to sunlight. Bacterial species have been previously discovered but the possibility of contamination couldn’t be ruled out during the previous expeditions. Here’s an excerpt on the discovery from the article:

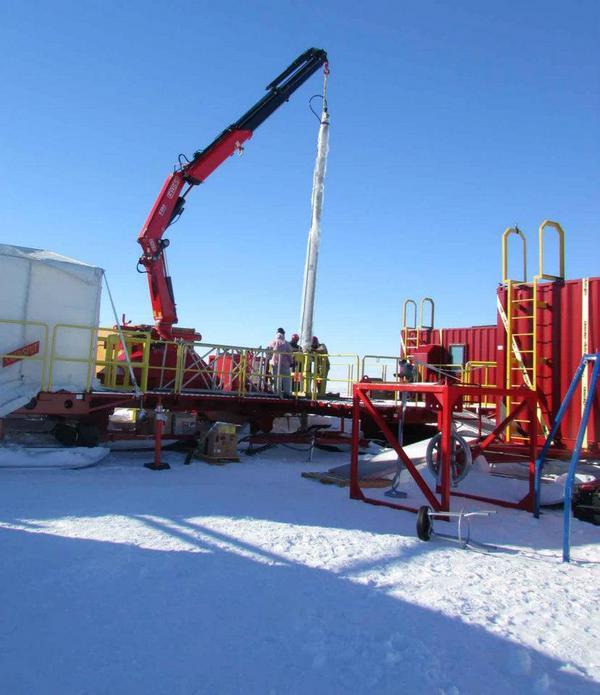

After drilling through a half-mile of ice into the 23-square-mile, 5-foot-deep Lake Whillans, the expedition scientists recovered water and sediment samples that showed clear signs of life, Dr. Priscu said, speaking from McMurdo Station in Antarctica on Tuesday. They saw cells under a microscope, and chemical tests showed that the cells were alive and metabolizing energy.

Dr. Priscu said that every precaution had been taken to prevent contamination of the lake with bacteria from the surface or the overlying ice. In addition, he said, the concentrations of life were higher in the lake than in the borehole, and there were signs of life in the lake bottom’s sediment, which would be sealed off from contamination.

Much more study, including DNA analysis, is needed to determine what kinds of bacteria have been found and how they live, Dr. Priscu said. There is no sunlight, so the bacteria must depend on organic material that has drifted into the lake from other sources — for instance, decaying microbes from melting glaciers — or on minerals in the rock of the Antarctic continent.

More here.