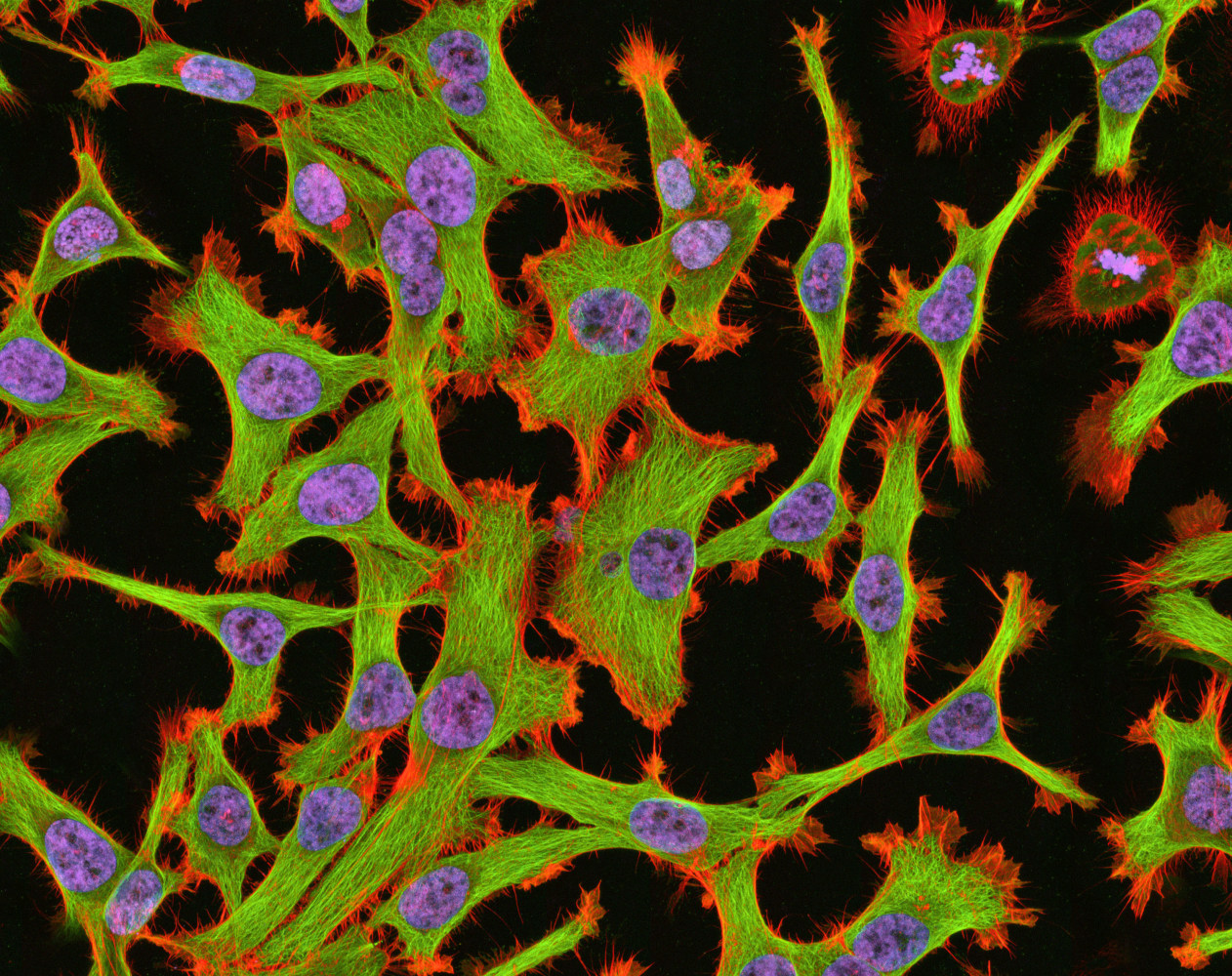

HeLa cells, cancer cells originally isolated from Henerietta Lacks, are among the most widely used cell lines for scientific research

Cell lines are frequently used in cancer research studies. They are pretty easy to maintain and they grow fast. The cell lines give us insight into some of the cellular pathways involved in tumor biology. They are often used as early-stage screens for potential cancer therapeutics, even though scientists know that they do not exactly share the same biology as an actual tumor. Cancer cells grow rapidly and they generate many mutations in the process. In a few cycles, the cells that you have in culture are different genomically than the cells that you started with. But still, having some information on what cells maybe doing in a tumor is better than no information at all.

Now Derek Lowe calls attention to a new study in Nature, which points out a potential problem with these cell lines in culture. In this new paper, the researchers found that not only are cancer cells different from the tumor that they started from, but there can be many differences within a strains of any given cell line. When they observed 27 strains of the MCF7 breast cancer line, the discovered rapid genetic diversification. They then looked at 13 additional cell lines and saw similar results. The genetic differences changed activation of gene expression, cell morphology and cell proliferation.

Derek Lowe sums up what this means for compound screening in cancer cell lines:

At least 75% of the compounds that showed strong inhibition of one MCF7 line were totally inactive against others. That’s going to confound experiments big-time, and this paper is a loud warning for people to be aware of this problem and to do something about it.